hemant sagar, one of one

fortune 19: from paris ateliers to delhi studios, a career stitched across continents

Hemant Sagar walks me through the new Genes office like someone giving a tour of a still-unfinished home. That’ll be a mirror, he gestures. And here, a photograph from a campaign a few seasons ago. The walls are bare for now, but the rooms are humming — racks of next season’s line being checked for fit, patterns hanging on spare hooks, pieces of decades-old couture archived on rails. In a small room by the entrance, Didier is painting onto a large sheet of vinyl. It smells like acrylic.

This is Genes Lecoanet Hemant, Sagar’s prêt-à-porter label — not named for denim, but for genetics. A label shaped by instinct, not industry. “You can wear them like jeans,” he jokes. “But they’re not blue at all.”

Sagar moves through it all with the rhythm of someone who’s done this before — not just the walkthrough, but the whole thing: the building, the team, the balancing act. “When we started in Paris, we were so few [we] knew everyone’s name. Now…” He trails off. “I try my best.”

He speaks like someone who’s always zooming in and out — from stitch to structure, from individual to system. The people matter. So does the lighting. So does the feeling of a seam pressed just right. It’s this combination — of intimacy and order, of vision and minutiae — that’s held his career together across decades, continents, and reinventions.

a house of his own

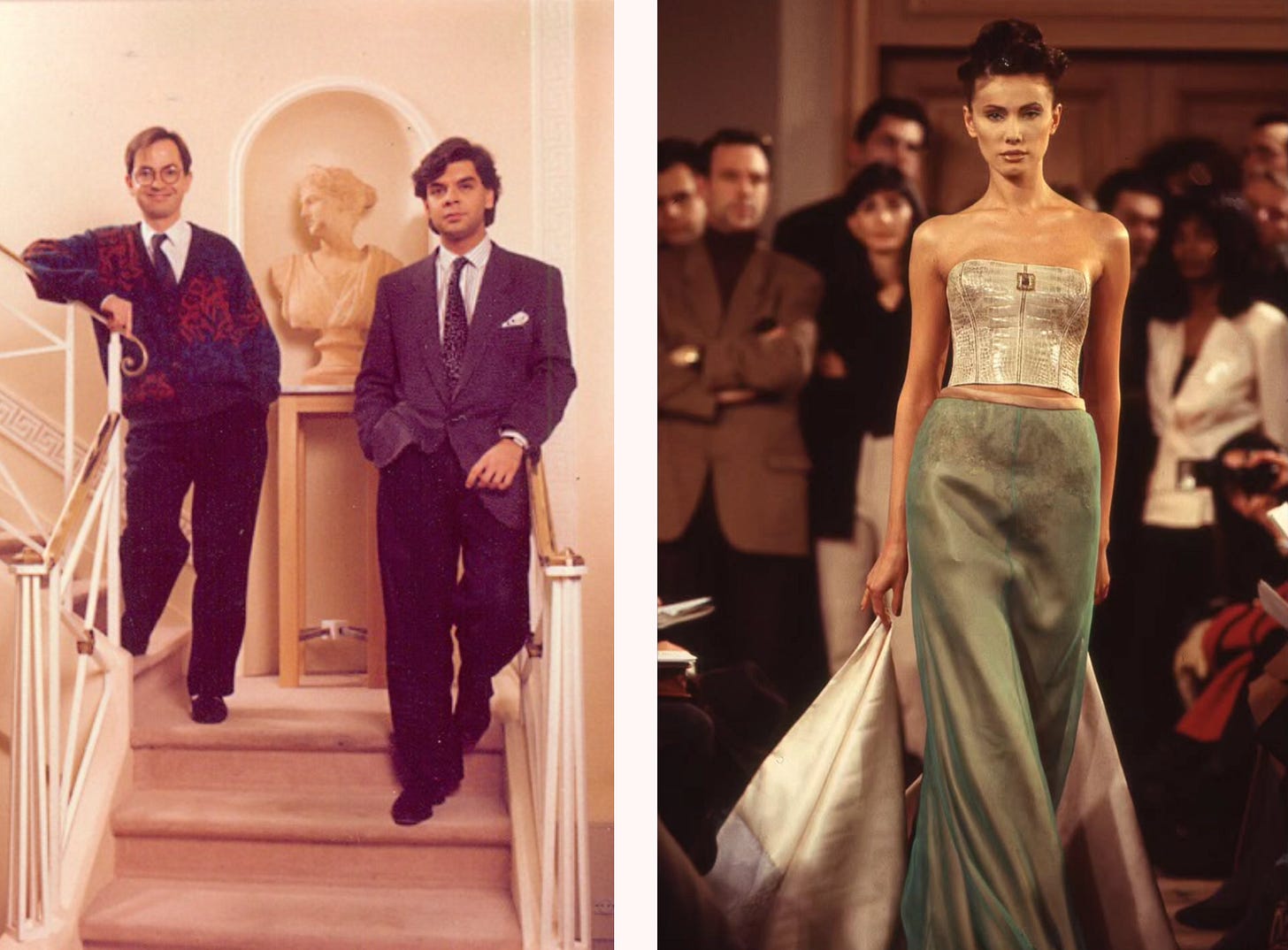

This isn’t the first space Hemant Sagar has built. Before Gurgaon’s concrete sprawl, there was Paris — a couture house launched with Didier Lecoanet, right next to Alaïa. “We didn’t knock on the door,” he remembers. “We just walked into couture, it felt daring.”

They weren’t supposed to be there. Sagar was barely out of his twenties, hadn’t apprenticed, hadn’t networked through the right salons — but that was the point. “We didn’t want to fuck our way through society,” he tells me, plainly. They just wanted to do their own thing.

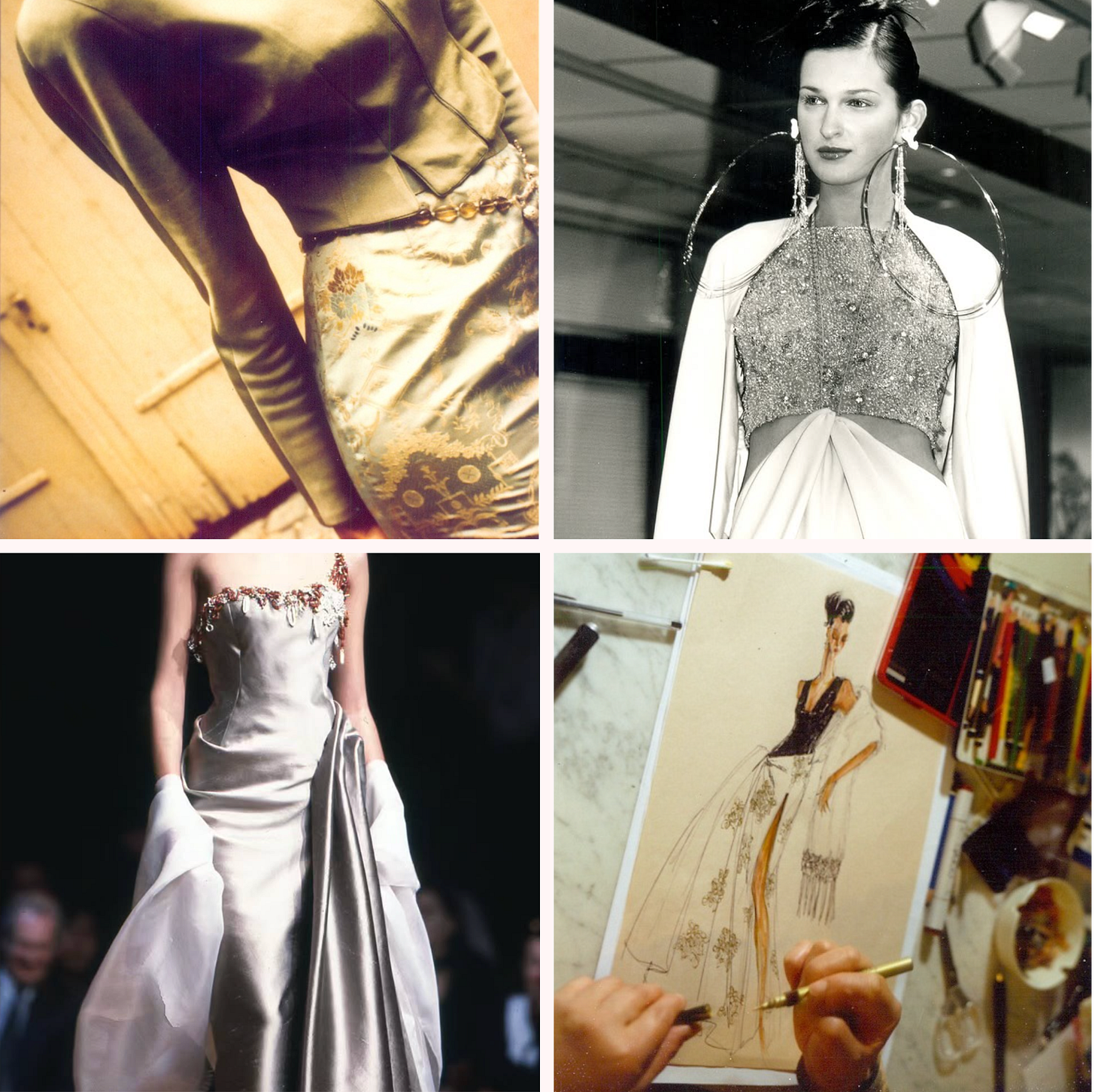

And they did. What followed was a two-decade career of deliberate defiance. Thirty-three couture collections. Articles in Figaro. A clientele that spanned royalty. The house operated more like a famille choisie than a business: fifty people at its peak, lunching together in pharmacist coats embroidered with Lecoanet Hemant. A Jack Russell between him and Didier on the motorbike to work. Madame Juliet, their head draper from Balenciaga.

“It was like a little family,” he reflects — not wistfully, but with the quiet certainty of someone who lived it fully. Eventually, the maison shuttered. He left Paris, as he puts it, “with one hand in front and one behind” — part of him carrying the past, part of him reaching for what’s next. But the work never stopped. He just changed cities.

Sagar likes to say he discovered beauty the way most children discover language — early, instinctively, and all at once. “I was just one and a half,” he recalls. “And totally addicted to anything that’s beautiful.” He speaks of it like devotion: mysterious, consuming, divine.

Born in Delhi to an Indian father and German mother, Sagar moved to Berlin at 15 — a shift that split his sense of home. “Your norm is not just one,” he reflects. “There are plenty of them.” That duality — sari and jacket, weaving and cutting — would eventually stitch itself into his work, not as contrast, but as cohesion.

Fashion came into focus through a glowing TV screen in Germany: a delayed Paris runway report, airing six months after the fact. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says, eyes bright. “It was like religion.” He didn’t know the designers. But he knew one thing: he had to go. To Paris. To the source. To whatever made that possible.

they said we couldn’t sew

Their debut couture collection was met with scepticism. Critics doubted they even knew how to thread a needle. “Paris wants you to apprentice at Givenchy, then Dior, then Chanel, have 25 references — and then maybe by 55, you might think about your first collection,” he recalls.

He was 27.

Yet, years later, some of those same critics changed their tune. “They wrote, I was the one who said they couldn’t sew. But now I see they really can.” Was it validating? “Of course,” he nods, without hesitation. But the praise came late — and didn’t erase the sense that they’d always been outsiders.

Still, Sagar wasn’t chasing prestige. “The most important thing in life is to be happy,” he offers. “Not to be rich, not to be successful — though that’s all very important. But if you’re happy, then maybe you’re already all those things.” He pauses. “I’m not the kind who needs to have stacks of money piled up somewhere. I like life.”

He talks about couture the way a sculptor talks about form — where every curve carries intention. “There’s an intelligence to haute couture,” he explains. “It touches all five senses. It’s the ultimate luxury, and it’s all about made-to-measure. It’s about honouring a single person. And you cannot flatter that person more. Because what you’re doing is — you’re looking at the person, and saying, wouldn’t you look taller if your décolleté was two centimetres lower? And just those seams, invisible, would make your waist come out. You make her lose three sizes — and she doesn’t even know why.”

That kind of sensitivity is still how he designs — less trend, more intuition. He calls them the Tintins of fashion: scrappy, sharp-eyed travellers chasing texture and instinct. His collections often start from a single flicker — a fabric, a gesture, a memory. He remembers a woman walking out of the sea in a wet sari on an Orissa beach: “It was the sexiest thing under the sun.” That image stayed with him for years. It didn’t appear on the runway as a sari, but as a feeling — refracted into shape and silhouette, yet even the most compelling vision can clash with a system built for conformity.

Fashion is fickle. And the system, unkind. Even as they made headlines for their ecological bridal gowns and architectural silhouettes, they remained outsiders.“We were the smallest house,” he recalls. “Spending a million francs while others spent twenty-five.” And they made it stretch. Instead of paying €8,000 a metre for Swiss embroidery, they flew to Bhutan to buy real yak. They zigzagged across continents in search of something rare, something with soul. “We were always travelling,” he says. “Always looking for something really special — for the poetry, not the flash.”

But even resourcefulness has its limits. For all their inventiveness, the margins stayed thin — and the system, unforgiving. Eventually, the maison shuttered. The team disbanded. The building went quiet.

paris…delhi

Sagar didn’t just leave a label behind — he left the entire ecosystem that sustained it. The ateliers, the drapers, the fabric houses, the esprit de corps. “You can’t do couture without a certain infrastructure,” he tells me. “And you can’t fake it.”

There was no grand exit. Just a quiet departure — and a one-way ticket to Delhi.

Starting over meant adjusting expectations. There were no multi-brand boutiques, no real culture of separates, and the market for couture was nearly nonexistent. “Everyone was saving for their daughter’s wedding,” he points out. “They didn’t want couture. They didn’t need couture.”

And yet, he still believed in elegance. In fit. In detail. If couture was about ritual, maybe ready-to-wear could be about rhythm — the everyday garment that shifts your posture by just enough. He wanted to make clothing that could move with the person wearing it. “Not that they’ll wear it every day,” he clarifies, “but when they do, I do think it could enhance their ambition.” Even just a little. A shift in posture. A subtle lift. The idea that clothing could carry that much charge — that was enough.

That was the beginning of his next act: not a comeback, but a recalibration. He no longer worked in the company — he worked on it. Sketches gave way to systems. Runways gave way to storytelling. And control gave way, slowly, to trust.

That shift — from ceremony to practicality, from couture to cadence — became Genes — a line designed for real life, with clothes that felt considered, modern, and emotionally attuned. Not watered-down couture — but something else entirely. A new rhythm. A different kind of elegance.

"It’s the eye of the field mouse versus the eye of the eagle flying over the field,” he explains. “It’s very different; your whole perspective changes.”

Even in prêt-à-porter, he still brings that couture instinct — not for embellishment, but for emotion. Clothes that feel intelligent. Clothes that make room for someone’s day, not their fantasy.

what you leave behind

When asked how he wants to be remembered, Hemant Sagar doesn’t hesitate. “If you look at people I really admire, most people today don’t even know who [they were]. So, let’s not have an illusion,” he says. “Let’s have fun while we’re here.”

He doesn’t say it sadly. Just plainly. There’s no nostalgia in him, no craving for monuments. If anything, he prefers the invisibility of it all — the idea that the work can keep moving, even when he doesn’t have to.

As for the legacy he chooses to leave behind? “Intercultural. Modern. Not traditional. Moral. Which sometimes we call rebellious.”

It’s a fitting description for someone who’s moved across borders, disciplines, and decades without ever asking for permission. And while his work lives in museums from Paris to London, he doesn’t think of legacy in grand terms — only that the work should speak for itself, wherever it ends up.

What matters to him now is clarity. That the codes are in place. That the people he’s chosen — and trained — know what belongs, what doesn’t, what to never put in front of him. “There’s a level of design they wouldn’t dream of showing me,” he points out. Not because he’s intimidating, but because they know better.

That’s legacy. Not being remembered, but being understood — beyond your presence.

And Genes is still evolving. He envisions it not as a static brand, but a living system — something that grows with its audience, season by season. “If I could make a statement, I’d do a show,” he tells me. “But I’d probably go for a one-minute fashion film now. It’s more effective.”

There are plans for expansion into the Middle East, new online collaborations, and shop-in-shops abroad.

But for now, Sagar is busy building and designing a new house in Thailand. Another space to shape. Another rhythm to follow.

“Life is a horse,” he tells me, like a closing line he’s known for years. “And if you don’t hold the reins, it’ll take you where it wants.”

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

Thank you for reading this profile on Hemant Sagar — it was such a joy speaking with him and tracing his journey from Paris couture to Delhi!

One of One is a series where I write about people I find interesting — doing things that feel original, personal, and worth paying attention to.

Check out Genes’ new Autumn/Winter 2025 collection, Codes, and their soon-to-open Mumbai store in Kala Ghoda. Codes is a study in what persists — a kind of dressing that carries meaning across seasons, grounded in continuity rather than the fleeting.

Stick around for more <3